Raindrops at the Tarrant Regional Water District’s headquarters get special treatment.

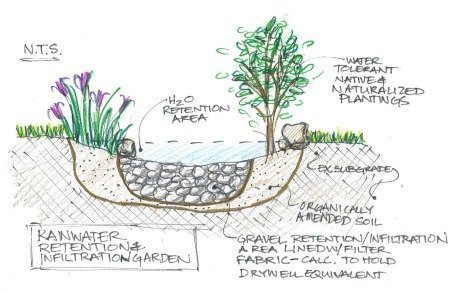

Some are collected in a raingarden before seeping into the soil. Rooftop raindrops are harvested and stored in cisterns. Then there’s the stormwater runoff that flows from a parking lot, into a meandering rock channel, that sends into a wetland, that treats it before releasing it.

Raingarden at TRWD

The District is using the Rainscapes built on its Fort Worth campus as an example of how commercial and residential landowners alike can efficiently, economically and ecologically protect water quality by using these landscaping methods to manage stormwater runoff.

“We want to lead by example, to showcase how it could be and how it can be an asset, not a liability or a burden,” said Michelle Wood-Ramirez, watershed coordinator for the District. “Our treatment train starts working on the water the minute rain hits the ground or the roof.”

Using green stormwater infrastructures like bioswales, permeable surfaces and native and adaptive plants will become more critical as the population grows and more of the open spaces are developed to support newcomers to the region.

“We want to demonstrate what it can look like and how it works with our own native ecosystems in Texas,” Wood-Ramirez said.

Drive onto the District’s campus and on the northwest side is a small park with curving permeable concrete pathways and a

Rock Channel Example

circular plaza with five benches. Surrounding the seating area are native plants, rock channels, gravel and a small raingarden that collects stormwater. To the plaza’s south are grassy knolls displaying five different types of turf grass; planted nearby are displays of native and adaptive plants. It’s a restful place that serves a dual purpose.

The 29,370-square-foot overlook is an example of green stormwater infrastructure that landowners can use. Besides aesthetically enhancing the landscape, this low impact development boosts the health of the soil and water: the rock channels slow down the flow of stormwater; the permeable sidewalks allow rain to seep in; the raingarden collects and cleans the water before allowing it to seep into the soil.

Other demonstration projects include bioswales in parking lot medians to slow down stormwater, allowing it to trickle into the ground. There’s also rainwater harvesting that instead of seeing rain simply go down the drain, it is directed into 5,000-gallon cisterns.

Then there’s the miniature wetlands on the campus’ southeast side.

Once a detention basin that didn’t work very well, it is now 41,500-square-foot wetlands that filters stormwater through carefully selected vegetation before releasing it into the Trinity River. It also turned what was an eyesore in the middle of the city into a safe haven for foxes, frogs, mallards, herons and egrets.

The District offers tours of its campus to show developers and homeowners how these landscape systems can be used on their own properties, not

only enhancing their beauty but often increasing their property value and saving them money in the long run.

Also available is the District’s Water Quality Guidance Manual. The manual, which applies to the 443 acres that make up the Trinity River channel and associated floodway, is described as a “cook book” that offers recommendations and resources on how to improve stormwater quality.

As the population increases, cleaning up that water will become crucial. It only takes a little bit of rain to create a real big mess. Solid waste such

as paper, cups and plastic bags get swept up in a storm’s runoff. Swirling in the water will be the slick, oily grit left on parking lots and roadways. Coming along for the ride will be dirt left in the gutter.

“If we don’t start doing this now, we won’t have a resilient and sustainable infrastructure and ecosystem for future generations,” Wood-Ramirez said. “If the population is going to double, we need to create these structures to protect our water quality, our infrastructure, and our health.”

Take a virtual tour of the TRWD Rainscape

Miniature wetlands on the campus’ southeast side.