For decades, North Texas lived – and thrived – on groundwater.

The vast Northern Trinity Aquifer underneath Fort Worth and Dallas contained trillions of gallons of water, with wells bringing it gushing to the surface. Then, as demand for water increased, and the groundwater was drawn down, the region turned to surface water to serve its communities.

But a pilot project by the Tarrant Regional Water District may make the aquifer a major player in the supply system again – this time by pumping water back into the massive rock formation.

An $8 million experimental Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR) project is expected to start this fall that will test the idea of storing millions of gallons of water in the aquifer sourced from the District’s East Texas reservoirs, turning the aquifer into a massive storage tank.

If the pilot project located at a northeast Fort Worth water treatment plant performs as expected, it could eventually lead to additional ASR wells being drilled across Tarrant County, helping the district store even more water for use during droughts and times of seasonal peak demand.

“I’m a big fan of the concept,” said TRWD Assistant General Manager Dan Buhman. “It is like banking. You take water when you are in times of plenty and you store it underground.”

TRWD Planning Director Wayne Owen said the District, which has been studying the idea for at least 20 years, needs to determine “if it’s a game changer.”

“There is no way to know until we punch holes in the ground and try it,” Owen said.

While the ASR program will not replace the District’s eventual need for building a new reservoir, it could postpone its construction for years by allowing the agency to balance, protect and efficiently use its existing water supply.

Others have successfully used aquifer storage and recovery systems.

In Texas, San Antonio, Kerrville and El Paso have systems for storage and recovery of groundwater. Bryan and Victoria are also developing ASR systems. There are at least 130 aquifer recharging programs across the United States.

“Using the aquifer for storage makes a lot of sense,” said TRWD board member Marty Leonard.

“I’ve always been excited about the prospect of it. And, if it can keep us from building another reservoir, that is all the better.”

TRWD board member Leah King said there frequently are new suggestions and technologies but that it comes down to “feasibility and expense.”

“It’s incumbent upon the district to be creative and to look at all manners and methods of ensuring we have adequate water supply for today’s population and for the continued expected growth over the next several decades,” King said.

City of artesian wells

Lying beneath Fort Worth and Dallas is the Northern Trinity Aquifer, a geological formation that stretches from the Colorado River to Oklahoma. Its sandstone makeup is capable of holding trillions of gallons of water and has the “storage capacity for water supplies that are unparalleled in Texas and the United States,” a report by CDM Smith states.

It was water from that aquifer that helped lure people to North Texas. Early residents bragged about the high-quality water coming from the ground. Fort Worth was the “city of artesian wells.” The Fort Worth Natatorium Hotel – with its Turkish baths – was popular in the 1890s. Towns like Balch Springs and Cedar Springs got their names from their artesian springs.

But increases in population led to more and more water being extracted, with many of the natural flowing artesian wells disappearing. The greatest drawdown – or the lowering of the groundwater level caused by pumping – occurred in Tarrant and Dallas counties.

While groundwater was still accessible, cities transitioned to surface water to provide an adequate supply. After the historic droughts of the 1950s tested the limits of local reservoirs, Richland Chambers and Cedar Creek reservoirs in East Texas were built.

“The Metroplex is the center of the significant drawdown of the Trinity aquifer,” Owen said. “The level underground where water is accessible at 1,200 feet; it’s dropped that far since Dallas and Fort Worth were founded.”

“The drawdown continued through the 20th Century and it’s now ground zero in Texas for groundwater drawdown, which sounds dire. But what that presents is the opportunity to potentially store surface water underground,” he said.

Feasibility and Expense

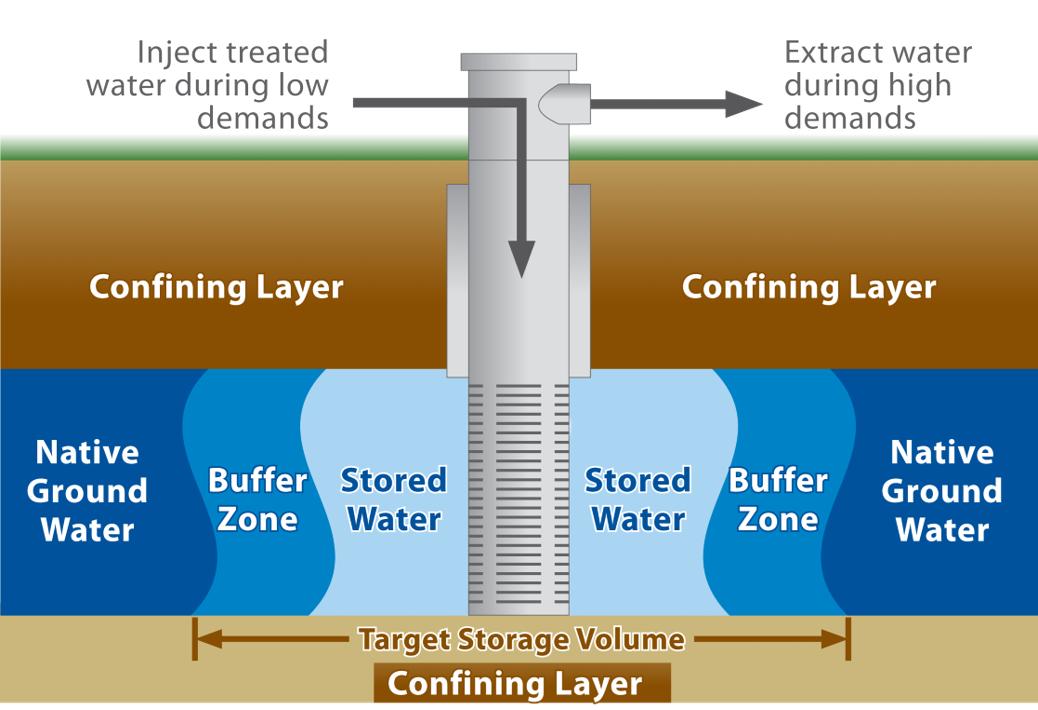

In an ASR system, water flows by gravity into an aquifer formation for storage through wells designed for both storage and recovery of water underground. Water is recovered by pumping from the well system when needed, either during seasonal demand fluctuations, or to protect against long-term drought conditions.

The District will get the water for its ASR pilot project from surplus supply available from the Richland Chambers and Cedar Creek reservoirs. Each year, the District is appropriated by state permit 485,000-acre feet of water from two reservoirs, but with TRWD’s current annual demands only being 360,000-acre feet, there is water supply to spare.

The District can’t carry over the 125,000-acre feet of unused water from one year to another, so it’s essentially lost. So, the question becomes: Why not store it underground? Water stored underground can accumulate like money in a savings account and withdrawn when needed.

As part of the 18-month pilot project, a 1,200-foot deep well will be drilled near the Trinity River Authority’s Tarrant County water treatment plant. Water brought from East Texas and stored in Lake Arlington will be treated in the plant and some of it will flow into a well head and down a pipe penetrating the aquifer.

The water will go into the aquifer gradually; if the water flows down the well too quickly, it can entrap air and cause the well to clog. Once underground, the treated surface water will remain separate from the native groundwater, essentially creating a large bubble, or water balloon.

Then, the experimental well will be cycle tested to see how much of the water can be recovered. Although most of the water is expected to be recoverable, a permit from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality will specify recovery of a percentage of the stored water.

Water quality also will be examined to determine if the treated water causes any chemistry issues in reacting with the native groundwater or the hydrogeological formation.

Recovered water will be treated as raw water from any other TRWD reservoir.

“In storing treated water, we could put it right back into the drinking water system. But we need to test the ASR to see how stored water is going to react,” Owen said. “It can mobilize metals and other constituent contaminants, so we want to make sure we do not bring back water that’s problematic.”

Economically attractive

The District examined a number of potential ASR sites before selecting the one in northeast Fort Worth, including the City of Fort Worth’s Rolling Hills Water Treatment plant and the City of Arlington’s Pierce Burch Water Treatment plant. The TRA’s Tarrant County plant supplies drinking water to Grapevine, Colleyville, Euless, Bedford and North Richland Hills.

Business case evaluation and engineering analysis, indicates it will take more than one ASR site, each with multiple wells, for the project to have a significant impact on the regional water supply system. One study suggests at least 150,000-acre feet of water needs to be stored for it to be cost effective.

Putting away that much water will require tapping other sources – including possibly storing raw instead of just treated water. Finding water to store will become more urgent as the surplus supply from East Texas declines because of increasing customer demands.

Even with those red flags, a larger ASR system could be pursued because it is “economically attractive and carries comparatively low risk of significant hurdles or delays,” according to a 2016 business case evaluation study written by CDM Smith and other engineering firms.

It could help the district postpone building another reservoir like Marvin Nichols with an estimated pricetag as high as $4.7 billion. In comparison, an ASR system also has very little infrastructure, unlike a reservoir which takes a dam, pipelines, and lots of land.

“It has a small footprint. It’s really just wells. It really makes our system much more resilient,” Buhman said.

Developing the ASR system to its fullest extent, making it a major player in the water supply system, however, will have to be done in “baby steps,” Owen said.

Still, he’s excited about the possibilities.

“Done on a scale that is meaningful and cost effective, it will be a game changer,” he said.